DEBUNKED -DEBUNKED -DEBUNKED -DEBUNKED -DEBUNKED -DEBUNKED -DEBUNKED -DEBUNKED -DEBUNKED -DEBUNKED -DEBUNKED -DEBUNKED

THE TRUTH REVEALED

PULLING THE CURTAIN BACK ON SEVEN WIDELY BELIEVED MYTHS

THE MYTH OF DISTINCT TASTE REGIONS ON YOUR TONGUE

The myth of distinct taste regions on the tongue is a popular misconception that suggests different areas of the tongue are responsible for detecting specific tastes such as sweet, sour, salty, and bitter. This idea has been debunked by scientific research, and it is now widely recognized that taste buds capable of detecting all basic tastes are distributed across the entire tongue. The concept of distinct taste regions gained prominence in the early 20th century when a German scientist named David P. Hanig published a paper suggesting that different taste sensations were localized to specific areas of the tongue. This idea was later popularized in textbooks and educational materials, leading to the widespread belief in a "taste map" of the tongue. However, more rigorous and comprehensive studies in subsequent years, including the pioneering work of Harvard psychologist Edwin G. Boring and others, demonstrated that taste receptors for all four primary tastes are evenly distributed throughout the tongue.

Taste buds are specialized structures found in the papillae on the tongue's surface, and each taste bud is capable of detecting a range of taste qualities.In reality, the perception of taste is a complex process involving the interaction of taste buds, olfactory receptors (responsible for smell), and other sensory factors. Taste receptors are sensitive to different molecules, and the brain integrates signals from these receptors to create the perception of specific tastes.The debunking of the myth of distinct taste regions highlights the dynamic and interconnected nature of our sensory systems, challenging long-standing misconceptions and contributing to a more accurate understanding of how we experience taste.

THE BELIEF THAT THE GREAT WALL OF CHINA IS VISIBLE FROM SPACE

The myth that the Great Wall of China is visible from space without aid has been widely perpetuated for many years. The notion that the Great Wall is the only human-made structure visible from space with the naked eye is, however, a misconception. This idea likely originated from earlier times when space travel and satellite imagery were not as advanced as they are today.

In reality, viewing the Great Wall from space without aid is extremely challenging, if not impossible. The width of the wall is relatively narrow, and its color and material are not significantly different from the natural terrain. Astronauts who have been in space have noted that it is difficult to spot the Great Wall with the unaided eye from the low Earth orbit.

The myth gained traction through various sources, including textbooks, travel guides, and even encyclopedias, which perpetuated the idea without proper scrutiny. It is essential to recognize that modern technology, such as satellite imagery, provides a much clearer and more accurate view of Earth from space than the human eye.

Astronauts have mentioned that other prominent human-made structures, like city lights, are more visible from space than the Great Wall. The misconception about the Great Wall's visibility from space highlights the importance of critically evaluating information and relying on accurate scientific knowledge rather than accepting popular beliefs that may not be based on facts.

THE MISCONCEPTION THAT BATS ARE BLIND

The misconception that bats are blind is a widespread myth that has persisted for centuries. This false belief likely stems from the fact that many species of bats are nocturnal and use echolocation to navigate and locate prey in the dark. However, we are here to clarify that bats are not blind, and in fact, they have eyes and can see.

Bats, like most mammals, have well-developed eyesight. While some species of bats have relatively small eyes and may rely more on echolocation for hunting and navigation, others have large eyes and good vision. The size and structure of a bat's eyes can vary depending on its specific species and ecological niche.

Echolocation is a remarkable adaptation that allows certain bat species to navigate and hunt in complete darkness. Bats emit high-frequency sounds and listen to the echoes that bounce back, enabling them to create a mental map of their surroundings. This ability is particularly useful for locating prey, avoiding obstacles, and finding roosting sites.

The myth of bats being blind likely arose due to the unfamiliarity and mystery surrounding these nocturnal creatures. Additionally, the association of bats with darkness and the use of echolocation may have contributed to the misconception. However, it is crucial to dispel this myth and recognize that bats are not blind; they have a range of sensory adaptations, including eyesight and echolocation, that make them highly efficient and successful mammals in various environments.

THE MYTH THAT SUGAR MAKES YOU HYPERACTIVE

The myth that sugar makes you hyperactive has been a long-standing belief, especially among parents and caregivers. The idea is that consuming sugary foods, such as candies, sodas, and sweets, leads to a burst of energy and hyperactivity in children. However, scientific research has consistently debunked this myth.

Numerous well-controlled studies have found no direct link between sugar consumption and increased hyperactivity. In fact, several double-blind studies, where neither the participants nor the researchers know who is receiving a particular treatment, have failed to show any significant difference in behavior between children who consume sugar and those who do not.

The misconception likely arises from the common observation that children tend to be more energetic and excitable after consuming sugary treats. However, this is more likely due to the psychological and social context surrounding the consumption of sugary foods, such as parties or celebrations, rather than the sugar itself.

What's more, sugar is a source of glucose, a type of sugar that is a primary energy source for the body and brain. Consuming sugar leads to a temporary increase in blood glucose levels, providing a quick burst of energy. However, this energy boost is relatively short-lived and is not associated with sustained hyperactivity.

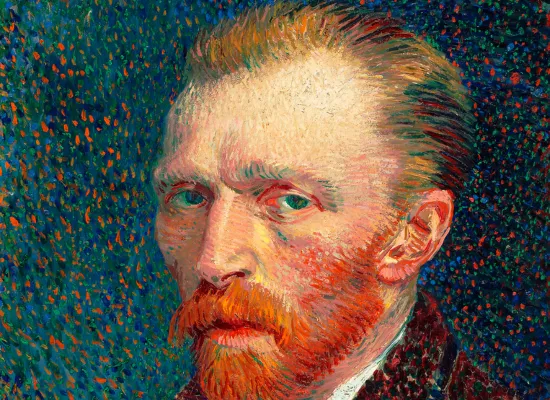

THE STORY THAT VINCENT VAN GOGH SEVERED HIS EAR FOR A LOVER

The story that Vincent van Gogh severed his ear for a lover is a well-known myth surrounding the famous Dutch artist. While it's true that Van Gogh did, in fact, mutilate his ear, the specific circumstances behind this act are more complex than the popular narrative suggests.The incident occurred in December 1888 in Arles, France, where Van Gogh was living and working at the time. The prevalent narrative often attributes the ear mutilation to a romantic dispute with a woman named Rachel, a local prostitute. However, historical accounts and scholarly research have provided a more nuanced understanding of the event.

The most widely accepted theory is that Van Gogh had a tumultuous relationship with his fellow artist Paul Gauguin, who was staying with him in Arles. The two artists had a strained friendship, marked by artistic differences and personal conflicts. On the night of the ear mutilation, it is believed that Van Gogh, in a fit of mental distress, severed part of his own ear with a razor.

The myth of Van Gogh mutilating his ear for a lover likely emerged from a combination of sensationalism, romanticization of the tortured artist archetype, and the complexities of Van Gogh's mental health. Van Gogh struggled with mental illness throughout his life, and his emotional and psychological challenges are well-documented in his letters to his brother Theo.

It's crucial to approach historical narratives about artists with a discerning eye just like other people in your life and to consider the broader context of their lives and mental states. The true motivations behind Van Gogh's ear mutilation remain somewhat speculative, but the evidence suggests that it was a complex and tragic episode in the artist's troubled life rather than a simple act of romantic sacrifice.

THE IDEA THAT HUMANS ONLY USE 10 PERCENT OF THEIR BRAINS

The idea that humans only use 10 percent of their brains is a common misconception that has been widely debunked by neuroscience. This myth has persisted for decades and has been perpetuated in popular culture, self-help books, and even in some educational settings.

In reality, neuroscientific research consistently demonstrates that the entire human brain is active and serves various functions. Modern brain imaging techniques, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET), allow scientists to observe brain activity in real-time. These studies consistently show that virtually all parts of the brain have identifiable functions, and no large, unused regions exist.

The 10 percent myth likely originated from misinterpretations of early neuroscience research or misattributions to famous figures like Albert Einstein. Over time, this idea became ingrained in popular culture, leading to the misconception that a vast portion of the brain remains dormant.

In truth, different areas of the brain are responsible for various functions, and the brain is highly interconnected. Even during activities that may seem mundane or automatic, multiple areas of the brain are engaged. Additionally, the brain's plasticity allows it to adapt and reorganize throughout life based on learning and experiences.

Dispelling the 10 percent myth is important for adopting a more accurate understanding of the complexity and capabilities of the human brain. Appreciating the full extent of brain function can contribute to a more informed perspective on neuroscience, education, and cognitive abilities.

The notion that it takes 21 days to break a habit

The idea that it takes 21 days to break a habit is a popular notion that has circulated widely in self-help and personal development circles. This concept is often attributed to Dr. Maxwell Maltz, a plastic surgeon, and author, who observed in the 1960s that it took his patients an average of 21 days to adjust to changes in their appearance.

However, the 21-day rule has been misinterpreted and oversimplified over time. Maltz himself did not claim that it takes exactly 21 days to form or break a habit; rather, he suggested that it takes a minimum of about 21 days for people to adjust to a new situation. Moreover, his observations were anecdotal and not based on rigorous scientific research.

Subsequent studies in habit formation and behavior change have provided a more nuanced understanding. Research conducted by Dr. Phillippa Lally at the University College London in 2009 found that, on average, it takes about 66 days for a new behavior to become automatic or to form a new habit. However, the duration varied widely among participants, with a range from 18 to 254 days.There are many people who quit smoking or quit drinking “cold turkey” and never touch that vice again. The key takeaway is that the time it takes to break a habit or establish a new one is highly individual and depends on various factors such as the complexity of the behavior, the individual's motivation, and the context in which the change is occurring.

In essence, while the 21-day rule provides a simple and memorable guideline, it is not a one-size-fits-all solution for habit change. Establishing or breaking habits requires patience, consistency, and an understanding of individual differences in behavior change.